Better Take a Look Again Jazz Standard

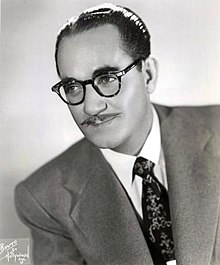

Richard Rodgers (left) and Lorenz Hart were responsible for a large number of 1930s standards, including "Blueish Moon" (1934), "My Romance" (1935) and "My Funny Valentine" (1937).

Jazz standards are musical compositions that are widely known, performed and recorded by jazz artists as part of the genre's musical repertoire. This list includes compositions written in the 1930s that are considered standards past at least one major fake volume publication or reference work. Some of the tunes listed were already well known standards past the 1940s, while others were popularized later. Where appropriate, the years when the most influential recordings of a vocal were made are indicated in the list.

Broadway theatre contributed some of the nearly popular standards of the 1930s, including George and Ira Gershwin's "Summertime" (1935), Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's "My Funny Valentine" (1937) and Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein Ii'southward "All the Things You Are" (1939). These songs yet rank among the most recorded standards.[1] Johnny Green'south "Torso and Soul" was used in a Broadway evidence and became a hit afterward Coleman Hawkins'due south 1939 recording. It is the about recorded jazz standard of all time.[ii]

In the 1930s, swing jazz emerged equally a dominant course in American music. Duke Ellington and his ring members composed numerous swing era hits that accept become standards: "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)" (1932), "Sophisticated Lady" (1933) and "Caravan" (1936), among others. Other influential bandleaders of this period were Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway and Fletcher Henderson. Goodman'south ring became well-known from the radio testify Let's Dance and in 1937 introduced a number of jazz standards to a wide audition in the first jazz concert performed in Carnegie Hall.[iii]

1930 [edit]

George Gershwin'due south songs take gained lasting popularity among both jazz and pop audiences. Among standards composed past him are "The Man I Love" (1924), "Embraceable You" (1930), "I Got Rhythm" (1930) and "Summertime" (1935).

- "Body and Soul"[4] [5] [6] [7] is a song composed by Johnny Dark-green with lyrics past Frank Eyton, Edward Heyman and Robert Sour. The song was used in the successful Broadway revue Three's a Oversupply and became an instant hit, despite beingness banned from the radio for well-nigh a yr for its sexually suggestive lyrics.[ii] The start jazz recording was past Louis Armstrong in 1930. Coleman Hawkins' 1939 recording consisted of iii minutes of improvisation over the song's chord progression with only passing references to the melody. Hawkins's rendition was the commencement purely jazz recording that became a commercial striking[8] and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1973.[9] The song is the nigh recorded jazz standard of all time.[ii]

- "But Non for Me"[10] was introduced past Ginger Rogers in the Broadway musical Girl Crazy. It was composed by George Gershwin with lyrics by Ira Gershwin. The song failed to attain meaning popular success, charting only once in 1942. However, information technology became popular in the jazz earth, especially for female person vocalists.[11]

- "Confessin'"[4] [12] was composed by Ellis Reynolds and Doc Daugherty, with lyrics by Al J. Neiburg. Louis Armstrong recorded it in 1930, and Rudy Vallée and Guy Lombardo both fabricated the charts with their versions the aforementioned year.[13] Saxophonist Lester Young recorded it several times during his career.[13] Country singer Frank Ifield had a number one striking with the vocal in the U.k. in 1963.[13] The song is as well known equally "I'm Confessin' (That I Love You)".[thirteen]

- "Embraceable You"[14] was originally composed past George Gershwin for an unfinished operetta East to West in 1928. It became a big hit afterward Ginger Rogers introduced it in the Broadway musical Girl Crazy, and was outset recorded by Fred Rich and His Orchestra. Lyrics were written by Ira Gershwin. Billie Holiday's 1944 recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2005.[9]

- "Exactly Similar You"[15] [16] was sung by Harry Richman and Gertrude Lawrence in Broadway show Lew Leslie's International Revue. It was composed past Jimmy McHugh with lyrics past Dorothy Fields. Louis Armstrong recorded the first jazz version in 1930. Benny Goodman's 1936 recording, sung by Lionel Hampton, revived interest in the song; the following twelvemonth it was recorded by Count Basie and Quintette du Hot Club de France.[17]

- "Georgia on My Mind"[4] [10] [xviii] is a song composed by Hoagy Carmichael with lyrics past Stuart Gorrell. Bix Beiderbecke played cornet on Carmichael's original 1930 recording. Frankie Trumbauer recorded the commencement hit version of the song in 1931. Ray Charles's version on The Genius Hits the Road (1960) was a number one hit, won ii Grammy Awards and is considered to be the definitive version of the song.[19] The song was designated as the state song of Georgia in 1979.[nineteen]

- "I Got Rhythm"[10] was composed by George Gershwin for the Broadway musical Girl Crazy, with lyrics past Ira Gershwin. Commencement-timer Ethel Merman's performance on Girl Crazy stole the limelight from leading lady Ginger Rogers. The song'due south I-six-2-V7 chord progression has been used in countless jazz compositions, and is normally known as "rhythm changes".[20] George Gershwin's last concert composition, Variations on "I Got Rhythm" was based on this song.[21]

- "Lazy River",[four] [22] a vocal by Hoagy Carmichael and Sidney Arodin,[23] was a hit for the Mills Brothers in 1941.[24] The Si Zentner Orchestra recorded it in 1962 and used it as their theme song.[24] Online music guide Allmusic describes it as "[e]asily one of the true popular classics of all time".[25] It is also known as "Up a Lazy River" or "Upwards the Lazy River".[23]

- "Love for Sale"[ten] is a song from Cole Porter'southward Broadway musical The New Yorkers. Its prostitution-themed lyrics were considered bad gustation at the fourth dimension, and the vocal was banned from the radio. The ban, nevertheless, only increased the vocal'southward popularity.[26] Porter himself was actually pleased that it could not be sung over the air.[27] In the original musical the song was first sung past Kathryn Crawford and after by Elizabeth Welch.[26] It was first recorded by Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians. The song took fourth dimension to catch on every bit a jazz standard, possibly considering information technology was 72 measures long. When Sidney Bechet recorded information technology in 1947, the song was non nevertheless a regular jazz number.[26]

- "Memories of You"[four] [28] [29] starting time appeared in the musical revue Blackbirds of 1930. It was composed past Eubie Blake and lyrics were written by Andy Razaf. It was introduced past Minto Cato on Broadway[30] and the first recording was made by Ethel Waters in 1930.[31] Louis Armstrong's 1930 recording was Lionel Hampton'southward debut functioning as a vibraphonist and rose to number 18 on the charts.[30] Hampton after recorded the melody again with Benny Goodman's jazz orchestra; this version has made the vocal a pop clarinet number.[30]

- "Mood Indigo"[4] [10] [32] [33] is a jazz song composed by Barney Bigard and Duke Ellington, with lyrics by Irving Mills. Bigard has admitted borrowing parts of the song from a composition called "Dreamy Dejection" by his teacher Lorenzo Tio.[34] The lyrics were written by Mitchell Parish, who then sold them to Mills'southward publishing company for a stock-still cost.[35] [36] When the song became a hitting, Parish was therefore left without royalties.[37] Ellington'southward 1930 recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1975.[9]

- "On the Sunny Side of the Street"[4] [10] [38] [39] [xl] was written past composer Jimmy McHugh and lyricist Dorothy Fields for the Broadway musical Lew Leslie'due south International Revue. Harry Richman sang it in the original revue.[41] Although the musical was a flop, "On the Sunny Side of the Street" became instantly popular. Richman and Ted Lewis charted with it in 1930,[41] and Louis Armstrong recorded his version in 1934. The vocal is readily associated with Armstrong today.[42] Tommy Dorsey and Jo Stafford both brought the vocal to the charts in 1945.[41] Jeremy Wilson argues that the song may really accept been composed by Fats Waller, who then sold the rights for information technology.[41]

1931 [edit]

- "All of Me"[4] [x] [43] [44] was written past Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons. It was introduced on the radio by vaudeville performer Belle Bakery who as well performed the song on stage in Detroit'due south Fisher Theatre, reportedly breaking into tears in mid-performance.[45] The first hit recording was fabricated by Mildred Bailey with Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra, and by February 1932 both Louis Armstrong and Ben Selvin had risen to the charts with the vocal in add-on to Whiteman.[45] The vocal was rarely performed after 1932 until Frank Sinatra recorded it in 1948 and performed it in the 1952 film Meet Danny Wilson.[45]

- "Beautiful Love" is a pop song composed by Wayne Rex, Victor Immature and Egbert Van Alstyne with lyrics by Haven Gillespie. Information technology was introduced by the Wayne King Orchestra in 1931.

- "I Surrender Dear" is the title song of a 1931 film starring Bing Crosby. It was composed by Harry Barris with lyrics past Gordon Clifford. Bing Crosby performed the song in the motion-picture show, and his recording with the Gus Arnheim Orchestra became his kickoff solo hit and helped him get a contract for his first radio bear witness.[46] The first jazz vocalizer to record the song was Louis Armstrong in 1931.[46] Thelonious Monk recorded it equally the sole standard on his 1956 album Brilliant Corners.[46]

- "Just Friends"[x] [47] is a ballad composed by John Klenner with lyrics by Sam Yard. Lewis. It was introduced by Red McKenzie and His Orchestra. The song rose to the charts twice in 1932; Russ Columbo's recording with Leonard Joy's Orchestra peaked at number fourteen, equally did a rendition by Ben Selvin and His Orchestra later on the same year. Popularized in mod jazz past Charlie Parker's 1950 recording, the song became pop among Due west Coast cool jazz artists in the mid-1950s. Chet Baker's 1955 version is considered the definitive song performance.[48]

- "Out of Nowhere"[4] [10] [49] was introduced past Bing Crosby and became his first number one hitting as a solo artist. The lyrics for the Johnny Light-green composition were written by Edward Heyman. Coleman Hawkins's 1937 recording with Benny Carter and Django Reinhardt was long the definitive version. The song'due south harmony has been reused in many jazz compositions, such as Tadd Dameron's "Casbah" and Fats Navarro's "Nostalgia".[50]

- "When It'due south Sleepy Time Down South"[51] is a song about the Great Migration, written by Clarence Muse, Leon René and Otis René. Information technology was originally offered to Knuckles Ellington, who did not consider the song to be his fashion and declined.[52] Louis Armstrong later adopted it as his theme song[53] and recorded it almost a hundred times during his career.[54] The song is also known as "Sleepy Time Down South".[51]

- "When Your Lover Has Gone" was written past Einar Aaron Swan for the film Blonde Crazy. Louis Armstrong made the first jazz recording of the song in 1931. The aforementioned year information technology was recorded past Gene Austin, Ethel Waters and Benny Goodman, and Austin'due south rendition was the first to hit the charts. Frank Sinatra included the vocal on his 1955 anthology In the Wee Small Hours. Sarah Vaughan made an uptempo recording in 1962 with Count Basie'southward ring.[55]

1932 [edit]

Virtuoso pianist Art Tatum by and large played Broadway and popular standards. He unremarkably radically reworked the songs and had the ability to make standards sound like new compositions. Tatum's influential pianoforte solos include "Tiger Rag", "Willow Weep for Me" and "Over the Rainbow".

- "Alone Together" is a ballad from Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz's Broadway musical Flight Colors. It was introduced past Jean Sargent on stage. A rendition past Leo Reisman and His Orchestra charted in 1932, and Artie Shaw made the get-go jazz recording in 1939. Dizzy Gillespie borrowed the harmony from the vocal'due south bridge for his 1942 composition "A Dark in Tunisia".[56]

- "April in Paris"[4] [10] [57] is a Broadway show tune from Walk a Trivial Faster, composed past Vernon Duke with lyrics by Yip Harburg. It was sung by Evelyn Hoey in the musical, merely did not become pop until later the Broadway production ended and blues singer Marian Chase started including information technology in her repertoire.[58] The offset recording was by Freddy Martin and His Orchestra in December 1933. Thelonious Monk'southward 1947 piano trio rendition helped popularize the song as a jazz vehicle.[58] Count Basie'southward 1955 recording became his biggest hit[58] and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1985.[9]

- "How Deep Is the Ocean? (How Loftier Is the Sky?)",[59] a song written by Irving Berlin, was first made a hit by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra with singer Jack Fulton. The song'due south jazz popularity was established by Benny Goodman'south 1941 recording with singer Peggy Lee. Coleman Hawkins made a popular jazz version in 1943, and Charlie Parker recorded it as a carol in 1947.[60]

- "I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Take chances with You"[iv] [61] [62] was composed past Victor Young with lyrics by Bing Crosby and Ned Washington. The starting time recording by Crosby became an immediate hit, reaching number five on the pop singles chart. Saxophonist Chu Drupe made an influential jazz recording with Cab Calloway in 1940. The song's name is often shortened to "Ghost of a Gamble".[63]

- "It Don't Mean a Affair (If It Ain't Got That Swing)"[4] [10] [64] [65] is a jazz vocal that singer Ivie Anderson introduced with the Knuckles Ellington Band. The lyrics for the Ellington composition were written past Irving Mills. The same year, a rendition by the Mills Brothers rose to the charts. The song's title introduced the term "swing" into common usage and gave name to the swing era.[66]

- "New Orleans"[67] is a vocal past Hoagy Carmichael. Get-go recorded by Bennie Moten's Kansas Urban center Orchestra and the Casa Loma Orchestra as an up-tempo number, the vocal just achieved success subsequently Carmichael recorded a slower version with vocaliser Ella Logan. The vocal was based on the chord progressions of "You Took Advantage of Me" and "Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams".[68]

- "Night and Day"[10] was written past Cole Porter for the musical Gay Divorce. It was introduced on phase past Fred Astaire, who also sang it in the 1934 movie The Gay Divorcee, based on the musical. The vocal remained popular throughout the swing era and charted v times in the 1930s and 1940s. It became Frank Sinatra's first hitting under his ain name in 1942.[69]

- "Willow Weep for Me"[four] [44] [70] is a song with music and lyrics by Ann Ronell. It was offset recorded by Ted Fio Rito and His Orchestra and, ii weeks later, by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra.[71] Fine art Tatum recorded the slice half-dozen times; his 1949 performance on Piano Starts Hither is ofttimes considered the definitive instrumental version of the song.[71] [72] Count Basie's "Taxi War Dance" was based on the song's harmony.[71] Ronell dedicated the song to George Gershwin.[71]

1933 [edit]

- "Don't Blame Me"[four] [10] [73] [74] was introduced in the musical revue Clowns in Clover and included in the 1933 film Dinner at Eight. The picture is often mistakenly given as the song'south origin. The first hit recordings were by Guy Lombardo and Ethel Waters in 1933. Nat King Cole recorded it several times as an instrumental, and had a striking with a 1944 vocal version. Charlie Parker fabricated an influential carol rendition in 1947. The song was composed by Jimmy McHugh with lyrics past Dorothy Fields.[75]

- "I Encompass the Waterfront", composed by Johnny Green with lyrics by Edward Heyman, was inspired past the 1932 novel of the same name past Max Miller. The song was included in the score of the 1933 picture show I Cover the Waterfront, and was first recorded by Abe Lyman and His Orchestra. Louis Armstrong, Joe Haymes, Eddy Duchin and composer Greenish all made recordings of the song in 1933, and Haymes's and Duchin's versions made the pop charts. Billie Holiday recorded the song many times during her career. Fine art Tatum recorded it as a solo piano piece in 1949 and returned to it several times.[76]

- "It'south Only a Paper Moon"[4] [77] [78] is a song from the short-lived Broadway show The Not bad Magoo, composed by Harold Arlen with lyrics by Yip Harburg and Billy Rose. Originally titled "If You Believed in Me", the current title was introduced in the 1933 movie Accept a Run a risk. The song first charted in 1933 with Paul Whiteman's and Cliff Edwards'south recordings. Nat King Cole recorded a trio operation of it in 1943, and both Ella Fitzgerald and Benny Goodman charted with the vocal in 1945.[79]

- "Moonglow"[iv] [lxxx] is a song equanimous by Will Hudson and Irving Mills, with lyrics written by Eddie DeLange.

- "Sophisticated Lady"[4] [10] [81] [82] is a jazz composition by Knuckles Ellington. Lyrics were later on added by Irving Mills and Mitchell Parish. Ellington's recording rose to number iii on the charts. Glen Gray and Don Redman also charted with the song in 1933. Lawrence Brownish and Toby Hardwick have claimed to have composed parts of the music; according to Stuart Nicholson'southward Ellington biography, the original composer credits included Ellington, Chocolate-brown, Hardwick and Mills, but simply Ellington was credited when the song was published.[83]

- "Yesterdays"[4] [44] [84] was composed past Jerome Kern for the Broadway musical Roberta, with lyrics by Otto Harbach. It was introduced by Irene Dunne. Non equally popular in the popular world as "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" from the aforementioned musical, it has enjoyed much more success in jazz circles. The song is often associated with Billie Holiday, who recorded information technology in 1944.[85]

1934 [edit]

- "Autumn in New York"[4] [86] was written for the Broadway musical Thumbs Up! past Vernon Duke, who contributed both music and lyrics for the song. Introduced on stage past J. Harold Murray and first recorded by Richard Himber and His Ritz-Carlton Hotel Orchestra, it was not until 1947 that the song became a hit with Jo Stafford's and Frank Sinatra's recordings. It became a pop jazz number in the 1950s after Charlie Parker recorded information technology for his album Charlie Parker with Strings.[87]

- "Blue Moon",[10] [88] composed past Richard Rodgers, was originally named "Prayer" and meant for the musical moving picture Hollywood Party. Lorenz Hart rewrote the lyrics two times for Manhattan Melodrama, and eventually it was sung by Shirley Ross as "The Bad in Every Man". It was later released commercially as "Blue Moon", with yet another set of lyrics, and was first recorded past Glen Grayness and the Casa Loma Orchestra. Hart disliked the last version, which nevertheless became his most popular vocal.[89] A 1961 rock and roll version past The Marcels sold a million copies and was included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame'southward list of 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Scroll.[90]

- "Solitude"[4] [10] [91] [92] is a Duke Ellington composition with lyrics by Eddie DeLange. Irving Mills received co-credit for the lyrics as Ellington'due south agent. Ellington claimed to have composed the song in 20 minutes. Two recordings fabricated the charts in 1935, one by Ellington and i by the Mills Blue Rhythm Band. Ellington's first vocal recording was made in 1940 with singer Ivie Anderson. The song is besides known as "In My Solitude".[93]

- "Fume Gets in Your Eyes"[4] [x] [94] is a song from Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach's Broadway musical Roberta. Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra's recording reached number ane on the popular charts in 1934. A one thousand thousand-selling, Billboard Hot 100 number one version was recorded past doo-wop grouping The Platters in 1958. Kern originally composed the song as a fast tap-dance number for his 1927 musical Bear witness Boat, and converted it into a ballad for Roberta. The song is particularly favored by piano players; Teddy Wilson made an early influential piano version in 1941.[95]

- "Stars Brutal on Alabama"[10] [96] was written by composer Frank Perkins and lyricist Mitchell Parish. Information technology was introduced by Guy Lombardo and His Majestic Canadians, and the outset jazz recording was made by Benny Goodman in 1934. Jack Teagarden recorded information technology many times; his outset recording was made with Goodman's orchestra in 1934 and he performed information technology in a 1947 Boston Symphony Hall concert with Louis Armstrong's All Stars.[97]

- "Stompin' at the Savoy"[iv] [10] [98] [99] is a jazz limerick past Edgar Sampson with lyrics past Andy Razaf.[100] First recorded by Chick Webb in 1934, information technology was popularized by Benny Goodman's 1936 recording.[101] Both Webb and Goodman received composer co-credit for the song.[100] Information technology was named afterwards the Savoy Ballroom in New York; the song title is mentioned in a commemorative plaque the ballroom's former place.[101]

1935 [edit]

Many 1930s standards were popularized by jazz vocalist Billie Vacation's recordings, including "These Foolish Things", "Embraceable You" and "Yesterdays".

- "Begin the Beguine" is a show tune from Cole Porter's Broadway musical Jubilee, start recorded by Xavier Cugat and His Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra and popularized past Artie Shaw's recording in 1938. It is considerably longer than the average vocal of the time (104 bars instead of the usual 32 bar AABA form). Fred Astaire and Eleanor Powell's tap dance to the tune in the 1940 motion-picture show Broadway Melody of 1940 became one of the most popular dance scenes on motion-picture show.[102]

- "In a Sentimental Mood"[four] [10] [103] [104] is a jazz vocal with music by Duke Ellington and lyrics past Manny Kurtz and Irving Mills. Ellington's biographer James Lincoln Collier argues that the melody was originally composed past Toby Hardwick.[105] The song is amid Ellington's most popular compositions.[105] Both Benny Goodman and the Mills Bluish Rhythm Band charted with the song in 1936. At one betoken, it was used as the theme song of nine different radio shows.[105]

- "Just One of Those Things" was introduced by June Knight and Charles Walters in Broadway musical Jubilee. The song was written past Cole Porter. Richard Himber and His Orchestra was the commencement to chart with the song in late 1935. Red Garland recorded it in London in 1936. Teddy Wilson fabricated a 1944 recording with Coleman Hawkins and recorded it the following year with the Benny Goodman Sextet. The vocal is also known every bit "It Was Just One of Those Things".[106]

- "My Romance"[4] [44] [107] is a vocal from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's Broadway musical Jumbo. Donald Novis and Gloria Grafton introduced the song on stage and recorded it with Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra.[108] Doris Mean solar day sang information technology in Jumbo's 1962 movie version.[109] Ben Webster recorded the song several times as a ballad. Bill Evans Trio's 1961 recording on Waltz for Debby is among the many medium-tempo swing renditions of the vocal.[108]

- "Summertime"[ten] was written by George Gershwin for the opera Porgy and Bess, based on a poem by DuBose Heyward. Introduced by Abbie Mitchell,[110] it is 1 of Gershwin's best-known compositions.[111] Sidney Bechet'southward 1939 hit record helped establish the Blue Note record label. One of the best-known renditions is by Miles Davis and Gil Evans on Porgy and Bess (1958).[110] Billy Stewart had a top ten hit with the song in 1966.[111]

- "These Foolish Things"[4] [44] [112] is a song from the British musical comedy Spread information technology Away, written past Harry Link, Holt Marvell and Jack Strachey. Information technology was introduced past French player Jean Sablon, who also recorded information technology in French every bit "Ces petites choses".[113] Billie Holiday recorded information technology in 1936 with Teddy Wilson and His Orchestra. Benny Goodman had a #1 hit with the song in 1936.[113] Lester Young made a 1952 recording with Oscar Peterson'due south trio, replacing the original melody almost completely.[114] The song is also known every bit "These Foolish Things Remind Me of You".[113]

1936 [edit]

- "Caravan"[10] [115] [116] is a jazz vocal with Heart Eastern influences, composed by Duke Ellington and Juan Tizol with lyrics by Irving Mills. It is mostly associated with Ellington, who recorded information technology many times in different arrangements.[117] It was a permanent part of Ellington's concert repertoire and was e'er played as the second number.[118] Barney Bigard made the first recording in 1936 with a band composed of members of Ellington'south orchestra.[119] The starting time vocal version to become a hit was made by Billy Eckstine in 1946.[120]

- "I Tin't Get Started"[4] [10] [121] was introduced by Bob Hope in the Broadway musical Ziegfeld Follies of 1936.[122] It was equanimous by Vernon Knuckles with lyrics by Ira Gershwin. Bunny Berigan'southward 1937 version became his most popular recording[123] and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1975.[9] Due to the success of Berigan'due south version, the piece is especially popular among trumpeters.[122] Billie Holiday recorded the song in 1938 with Lester Immature, and Immature fabricated a recording with his ain trio in 1942.[122] The song is besides known as "I Can't Get Started with Y'all".[122]

- "Pennies from Heaven"[4] [10] [124] was written by Arthur Johnston and lyricist Johnny Burke for the flick Pennies from Sky. Information technology was introduced by Bing Crosby, whose version remained on the height of the charts for 10 weeks and was nominated for an University Honour for Best Original Song. Lester Young played on Count Basie'due south 1937 recording and recorded the vocal several times in the 1940s and 1950s.[125]

- "Sing, Sing, Sing" is frequently associated with swing jazz bands, specially Benny Goodman's. The piece was performed in Goodman'due south 1938 Carnegie Hall concert[126] and was often used as the closing number in his live performances.[127] Written by Louis Prima and originally titled "Sing, Bing, Sing" as a reference to Bing Crosby,[126] the song is also known as "Sing, Sing, Sing (With a Swing)".[128]

- "There Is No Greater Dear"[four] [129] [130] is an Isham Jones limerick with lyrics by Marty Symes. Released by the Isham Jones Orchestra as a B-side to "Life Begins When Yous're in Love", it was the band's terminal hit before Woody Herman took over as bandleader. The starting time jazz recording was made by Duke Ellington.[131] A part of the song's melody was borrowed from Pyotr Tchaikovsky's Pianoforte Concerto No. ane.[132]

- "The Way You lot Expect Tonight"[4] [44] [133] was introduced by Fred Astaire in the film Swing Time. Information technology was composed by Jerome Kern with lyrics by Dorothy Fields. Astaire'south recording reached number one on the charts and the song won the Academy Award for Best Original Song. Billie Vacation recorded it with Teddy Wilson's orchestra in 1936. Benny Goodman made a version with Peggy Lee in 1942 and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers recorded their version in 1954. Johnny Griffin performed the piece with John Coltrane and Hank Mobley on the 1957 anthology A Blowin' Session.[134] Kern wrote the vocal'due south melody in counterpoint with "A Fine Romance"; the songs are sung together on the film'south endmost scene.[135]

1937 [edit]

- "Easy Living",[4] [136] a ballad composed by Ralph Rainger with lyrics past Leo Robin, was written for the film Easy Living and included on the soundtrack of the 1940 pic Remember the Dark.[137] It is most closely associated with Billie Holiday, who recorded information technology with Teddy Wilson'south Orchestra in 1937.[138]

- "A Foggy Twenty-four hours"[10] was written by George and Ira Gershwin for the musical flick A Damsel in Distress. Information technology was introduced in the moving-picture show by Fred Astaire, whose recording rose to number three on the charts. Bob Crosby'due south orchestra charted with the vocal in 1938.[139] The song is associated with London and begins with the chimes of the Big Ben.[140] It is also called "A Foggy Day in London Town".[139]

- "Have You Met Miss Jones?"[4] [10] [141] is a carol from the Broadway one-act I'd Rather Be Right, introduced on stage by Joy Hodges and Austin Marshall.[142] The song was composed by Richard Rodgers with lyrics by Lorenz Hart. Its span may have served as an inspiration to John Coltrane's 1959 limerick "Giant Steps".[143] Female singers often sing it as "Take You Met Sir Jones?".[142]

- "My Funny Valentine"[4] [10] [144] is Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's prove tune from the Broadway musical Babes in Arms. It was introduced on stage by Mitzi Green. Hal McIntyre and His Orchestra was the first to nautical chart with the song in 1945.[145] Frank Sinatra recorded a hit version in 1955, and later the song became readily associated with his alive performances. Other influential versions were recorded by Chet Baker (on My Funny Valentine, 1954) and Miles Davis (on Cookin', 1956).[145]

- "Nice Work If You Can Get It[4] was written by George and Ira Gershwin for the musical pic A Dryad in Distress. Information technology was introduced in the pic by Fred Astaire and has been recorded many times by jazz singers and pianists.[146]

- "In one case in a While"[ten] [147] is a composition by Michael Edwards with lyrics by Bud Green. It became a hit for Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra, whose recording stayed at the top of the charts for fourteen weeks. It was subsequently taken to the charts by Horace Heidt in 1937, Louis Armstrong in 1938, Patti Page in 1952 and doo-wop group The Chimes in 1961.[148] Rahsaan Roland Kirk is credited with reviving interest in the song amid jazz musicians with his 1965 recording, which mixed the original with Heart Eastern harmony.[148] [149]

- "I O'Clock Jump" is an instrumental twelve-bar blues composition by Count Basie. Used as the signature slice of Basie'southward band, it is strongly associated with the swing era and remains ane of the all-time-known compositions of the menstruation.[150] Saxophonist Buster Smith wrote a part of the composition, merely was denied co-credit by Basie.[151] [152] "1 O'Clock Bound" was taken to the charts by Harry James in 1938 and by the Metronome All-Stars in 1941. Benny Goodman gave an influential performance of information technology in his 1938 Carnegie Hall concert.[153]

- "Some Mean solar day My Prince Will Come"[4] [44] [154] was written by composer Frank Churchill and lyricist Larry Morey for Walt Disney's animated flick Snowfall White and the Seven Dwarfs. The first jazz recordings were by Donald Byrd and The Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1957. Nib Evans has recorded the song several times. Miles Davis'due south rendition on the anthology Anytime My Prince Will Come (1961) is notable for John Coltrane's memorable solo.[155]

- "They Tin't Take That Abroad from Me"[10] is a song from the musical film Shall Nosotros Dance, composed by George Gershwin with lyrics by Ira Gershwin. It was introduced by Fred Astaire, whose recording with the Johnny Dark-green Orchestra stayed at number one for 10 weeks. A famous version was recorded by Charlie Parker in 1950 and released on Charlie Parker with Strings.[156]

1938 [edit]

- "Cherokee"[158] [159] is a jazz song originally written past Ray Noble as a part of a larger Indian Suite. Information technology became a hitting for Charlie Barnet in 1939 as an instrumental. Barnet adopted an extended version of it into his theme song, credited to himself and titled "Redskin Rhumba". Don Byas recorded the slice in 1945, and the same twelvemonth Charlie Parker used its harmonic progression in his composition "Ko-Ko". Buddy DeFranco's "Swinging the Indian" is also based on the same chord progression. The song is besides known as "Indian Dear Song".[160]

- "Heart and Soul"[161] [162] is a Hoagy Carmichael composition with lyrics by Frank Loesser. It was first performed past Larry Clinton and His Orchestra featuring Bea Wain in the short moving-picture show A Song Is Born; their version charted at number 1 in 1939.[163] The song has been recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, Dean Martin, and Dave Brubeck, among others.[163] It has get a popular piece among apprentice pianists.[164]

- "Love Is Here to Stay" was George Gershwin's last composition, written for the musical film The Goldwyn Follies. Lyrics were provided by Ira Gershwin. The song gained little attention from The Goldwyn Follies and is amend known for the 1952 film An American in Paris.[165] The vocal was originally titled "Our Honey Is Here to Stay"; Ira Gershwin after said that he would have wanted to change the title back to the original one if the song had not already become pop under its new name.[166]

- "The Nearness of You"[4] [167] was composed by Hoagy Carmichael with lyrics by Ned Washington. It was meant to be included in the film Romance in the Rough, which was never produced. The first hit version was fabricated past Glenn Miller and His Orchestra in 1940. Sarah Vaughan recorded the vocal in 1949 and several times afterwards. Charlie Parker recorded information technology alive with Woody Herman's Orchestra in 1951.[168]

- "Sometime Folks" was equanimous by Willard Robison with lyrics past Dedette Lee Hill, the wife and occasional colleague of Billy Hill. It has been recorded many times by vocalists and instrumentalists and its most famous jazz version is by trumpeter Miles Davis on Someday My Prince Volition Come up (1961).[169] [170]

- "Prelude to a Kiss"[10] [171] [172] is a jazz carol composed past Duke Ellington with lyrics by Irving Mills and Mack Gordon. It was first recorded equally an instrumental by the Knuckles Ellington Orchestra featuring Johnny Hodges, who later recorded information technology with his own orchestra and vocaliser Mary McHugh. The limerick was based on a melody past Ellington's saxophonist Otto Hardwick.[173]

- "September Song"[4] [174] [175] was introduced by Walter Huston in the Broadway musical Knickerbocker Holiday. Information technology was composed past Kurt Weill with lyrics past Maxwell Anderson. Later striking recordings were made by Frank Sinatra in 1946 and Sarah Vaughan in 1954. Artie Shaw recorded information technology in 1945 with a big band featuring saxophonist Chuck Gentry. Don Byas made a 1946 recording with his quartet. Guitarist Django Reinhardt recorded the song four times, starting in 1947.[176]

- Cheers for the Memory was introduced in the film The Big Circulate of 1938 which earned the Academy Laurels for All-time Original Song of 1938. Information technology was equanimous by Ralph Rainger with lyrics by Leo Robin and performed in the film by Bob Hope and Shirley Ross.[177] Hit recordings were made by Shep Fields and his Rippling Rhythm Orchestra and by Bob Hope himself who adopted the composition as his signature vocal at the close of his USO tours in Europe during Earth War 2.[178] [179] [180] Over the decades the song was often recorded and remains a standard in the jazz repertoire to this twenty-four hours.[181] [182]

- "You Get to My Head" was written by composer J. Fred Coots and lyricist Haven Gillespie and introduced by Glen Grey and the Casa Colina Orchestra, who charted at number nine in 1938. Teddy Wilson with vocalist Nan Wynn charted with it in 1938, as did Larry Clinton and His Orchestra with Bea Wain. The song's harmonic composure has been praised by critics, who often describe Coots as a "one-hit wonder" despite his "Santa Claus Is Coming to Town" existence fifty-fifty more popular in terms of mass appeal.[183]

1939 [edit]

Clarinetist and bandleader Benny Goodman popularized many of the 1930s standards, including "Darn That Dream", "How Deep Is the Ocean", and "Stompin' at the Savoy".

- "All the Things Yous Are"[four] [10] [44] [184] is a vocal from Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II's Broadway musical Very Warm for May. Kern first felt the song, with its constantly shifting tonal centers, was too complex for mass appeal. However, information technology has enjoyed lasting popularity since then and is at present one of the almost recorded standards.[185] The song's chord progression has been used for such tunes every bit "Bird of Paradise" past Charlie Parker and "Prince Albert" by Kenny Dorham.

- "Darn That Dream"[44] [186] was composed past Jimmy Van Heusen for the Broadway musical Swingin' the Dream. Lyrics were written by Eddie DeLange. Although the musical was a thwarting, Benny Goodman's version of the vocal featuring vocalist Mildred Bailey was a number one hit.[187]

- "Frenesi"[4] [188] [189] is a Latin jazz composition by Alberto Dominguez. Originally composed for the marimba, jazz arrangements were later fabricated by Leonard Whitcup and others. A 1940 hit version recorded by Artie Shaw with an arrangement by William Grant Yet was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2000.[9]

- "I Didn't Know What Time It Was"[190] was sung by Richard Kollmar and Marcy Westcott in the Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart musical Too Many Girls. Benny Goodman recorded the first jazz version in 1939 with vocaliser Louise Tobin.[191]

- "I Thought About You"[4] [44] [192] [193] was composed by Jimmy Van Heusen with lyrics by Johnny Mercer. Mildred Bailey recorded the first striking version with the Benny Goodman Orchestra. Guitarist Johnny Smith recorded it in the 1950s for the Roost label. Miles Davis included the song on his 1961 album Someday My Prince Will Come.[194]

- "In the Mood"[195] [196] is a jazz composition by Joe Garland based on Wingy Manone'southward "Tar Paper Stomp". Andy Razaf wrote the lyrics for the song. Garland recorded "In the Mood" with Edgar Hayes and offered it to Artie Shaw, who never recorded the piece. It was popularized by the Glenn Miller Orchestra in 1939. The last arrangement was the upshot of work by Garland, Miller, Eddie Durham, and pianist Chummy MacGregor, although only Miller profited from its financial success.[197] The song remains popular and is almost ever performed as an instrumental.[198]

- "Moonlight Serenade"[10] [199] [200] was composed past Glenn Miller with lyrics past Mitchell Parish. Miller's orchestra used information technology every bit their signature tune,[201] and their recording charted at number three in 1939.[202] The vocal was recorded by rhythm and blues group The Rivieras in 1959.[202] Carly Simon sang it on her 2005 album Moonlight Serenade.[203]

- "Over the Rainbow"[ten] [204] is a ballad introduced by Judy Garland in the motion picture The Wizard of Oz, composed by Harold Arlen with lyrics by Yip Harburg. Information technology was an immediate hit: iv different versions, including Garland's, rose to top 10 within a month after the film'due south release. An influential piano solo recording was made by Art Tatum in 1955, and a live solo piano recording was released by singer-songwriter Tori Amos in 1996. The song is also known as "Somewhere over the Rainbow".[205]

- "Something to Live For"[206] is a jazz ballad written by Billy Strayhorn. Based on a poem the composer had written as a teenager,[207] the song was introduced by Knuckles Ellington's orchestra with composer Strayhorn on the piano. Ellington was co-credited with the composition.[208] The song has been recorded past Ella Fitzgerald, who has called it her favorite vocal.[209]

- "What's New?"[4] [10] [44] [210] started out as an instrumental titled "I'm Free", composed by Bob Haggart when he was playing in Bob Crosby's Orchestra, and was later retitled when Johnny Burke wrote lyrics for it. The song was introduced by Crosby, and other hit versions from 1939 include Bing Crosby's and Benny Goodman's renditions.[211] Australian singer Catherine O'Hara recorded the song in 1966 with her own lyrics, also titled "I'1000 Free".[211]

- "Woodchopper's Ball"[212] is a jazz composition by Joe Bishop and Woody Herman. Introduced by the Woody Herman Orchestra, it was the ring's first and biggest hit selling over a meg records.[213] [214] The original recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002.[nine] The composition is also known as "At the Woodchopper's Ball".[214]

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Peak fifty most recorded standards". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "Body and Soul". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "Jazz History: The Standards (1930s)". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i j k l yard northward o p q r south t u v westward x y z aa ab air-conditioning advertizement ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Listed in The Existent Vocal Book.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume I, p. 57.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume Ii, p. 29.

- ^ The New Existent Book, Volume Iii, p. 55.

- ^ Kirchner 2005, p. 185

- ^ a b c d e f g "Grammy Hall of Fame". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved ii April 2011.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i j k l m n o p q r southward t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Listed in The Real Jazz Book.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "But Not for Me". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty February 2009.

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume Two, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d Burlingame, Sandra. "I'g Confessin' That I Love You". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Embraceable You". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume Three, p. 116.

- ^ The New Real Volume, Book II, p. 98.

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "Exactly Like You". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume II, p. 145.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "Georgia on My Mind". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "I Got Rhythm". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty Feb 2009.

- ^ Greenberg 1998, pp. 152–155

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume I, p. 242.

- ^ a b "Lazy River". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ a b Studwell & Baldin 2000, p. 127

- ^ Matthew Greenwald. "Lazy River song review". AllMusic. Retrieved three May 2009.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "Beloved for Sale". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Wilder & Maher 1972, p. 229

- ^ The Real Volume, Book Two, p. 260.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume 2, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "Memories of You". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ Dryden, Ken. "Memories of You lot". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume I, p. 279.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume Two, p. 214.

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "Mood Indigo". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (i February 1987). "Theater; Mitchell Parish: A Way with Words". The New York Times . Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Tucker & Ellington 1995, pp. 338–340

- ^ Bradbury 2005, p. 31

- ^ The Real Book, Volume II, p. 298

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume III, p. 312

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume Two, p. 277.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Jeremy. "On the Sunny Side of the Street". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Forte 1995, p. 251

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k Listed in The New Real Book, Book I.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "All of Me". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "I Surrender Dear". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The New Existent Volume, Volume Three, p. 193.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Just Friends". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume I, p. 318.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Out of Nowhere". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty Feb 2009.

- ^ a b "When Information technology'due south Sleepy Time Down Southward". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Clayton 1995, p. 61

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 42

- ^ Hersch 2008, p. 199

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "When Your Lover Has Gone". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Lonely Together". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 32

- ^ a b c Burlingame, Sandra. "Apr in Paris". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 13 Dec 2010.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume 3, p. 150.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "How Deep Is the Bounding main? (How High Is the Heaven?)". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume Ii, p. 173.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume III, p. 132.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "(I Don't Stand a) Ghost of a Take chances (With Y'all)". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 224.

- ^ The New Real Book, Book II, p. 161.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Information technology Don't Mean A Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ "New Orleans". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Sudhalter 2003, p. 151

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Night and Day". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume Ii, p. 426.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Jeremy. "Willow Weep for Me". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Willow Cry for Me". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Book I, p. 121.

- ^ The New Existent Book, Volume Iii, p. 111.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Don't Blame Me". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "I Cover the Waterfront". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx December 2010.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume II, p. 209.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume II, p. 162.

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "It'southward Just a Paper Moon". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ The Real Book, Book I, p. 244.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume I, p. 376.

- ^ The New Existent Volume, Volume Two, p. 337.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Sophisticated Lady". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty December 2010.

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume I, p. 454.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Yesterdays". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume I, p. 38.

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "Autumn in New York". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ The New Existent Book, Book Three, p. 47.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Blue Moon". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty February 2009.

- ^ "Influential Rock Musicians from 1951 to 1963". Aces and Eights. Archived from the original on xxx Jan 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 366.

- ^ The New Existent Book, Book III, p. 346

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "Confinement". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume II, p. 354.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Fume Gets in Your Eyes". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume Iii, p. 354.

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "Stars Fell on Alabama". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 385.

- ^ The New Real Volume, Volume 3, p. 359.

- ^ a b Shaw 1989, p. 181

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "Stompin' at the Savoy". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx February 2009.

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "Begin the Beguine". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume I, p. 207.

- ^ The New Existent Book, Volume III, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "In a Sentimental Mood". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Just 1 of Those Things". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Existent Book, Book I, p. 289.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "My Romance". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Hischak 2007, p. 190

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "Summer". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 22 Apr 2011.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Summertime". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ The Existent Volume, Book 2, p. 392.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jeremy. "These Foolish Things". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved ii May 2011.

- ^ Hodeir & Pautrot 2006, p. 107

- ^ The Real Book, Book 2, p. 77.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume III, p. 73.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Caravan". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved two May 2011.

- ^ "Juan Tizol". All Nigh Jazz. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "Barney Bigard". JazzBiographies.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "Juan Tizol". JazzBiographies.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 184.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Jeremy. "I Can't Get Started (with You)". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Studwell & Baldin 2000, pp. 21–22

- ^ The Real Book, Volume II, p. 309.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Pennies from Heaven". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ a b Grudens 2005, p. 41

- ^ Stanton 2003, p. 361

- ^ "Sing, Sing, Sing". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Book I, p. 406.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume Two, p. 366

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "There Is No Greater Love". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved sixteen May 2011.

- ^ Studwell & Baldin 2000, p. 187

- ^ The Real Volume, Book Ii, p. 415.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "The Way Y'all Await This night". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty February 2009.

- ^ Banfield & Block 2006, pp. 273–274

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 127.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Like shooting fish in a barrel Living". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Hood, Al. "Clifford Brown: Easy Living". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "A Foggy Twenty-four hour period". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Forte 1995, pp. 166–167

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 172.

- ^ a b Burlingame, Sandra. "Take You Met Miss Jones". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "Giant Steps". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 27 Apr 2009.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume I, p. 287.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "My Funny Valentine". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Gioia 2012, pp. 295–297

- ^ The New Real Book, Book II, p. 278.

- ^ a b Burlingame, Sandra. "Once in a While". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "Rip, Rig and Panic". AllMusic. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "One O'Clock Leap". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Driggs & Haddix 2006, p. 168

- ^ Daniels 2006, p. 178

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "One O'Clock Bound". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Book I, p. 367.

- ^ Burlingame, Sandra. "Anytime My Prince Volition Come up". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "They Can't Have That Abroad from Me". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Obituaries- Shep Fields Dies on news.google.com

- ^ The Real Volume, Book I, p. 77.

- ^ The New Existent Volume, Book Ii, p. 47.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Cherokee (Indian Love Vocal)". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ "Center and Soul". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume III, p. 142.

- ^ a b Fishko, Sara (31 December 2006). "The Bouncy Joy of 'Heart and Soul'". NPR Music. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ Studwell 1994, p. 56

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Dearest Is Hither to Stay". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 Feb 2009.

- ^ Furia 1997, p. 234

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume II, p. 285.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "The Nearness of You". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Gioia 2012, pp. 308–310

- ^ Maycock, Ben. "One-time Folks". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved eleven September 2018.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 331.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume Iii, p. 294.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Prelude to a Kiss". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume 2, p. 344.

- ^ The New Real Volume, Volume 2, p. 318.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "September Vocal". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved twenty February 2009.

- ^ The Large Broadcast of 1938 - "Thanks For the Memory" sung in the film by Bob Hope and Shirley Ross with the Shep Fields Orchestra in Hollywood Musicals Twelvemonth past Year by Stanley Light-green, Milwaukee WI, 1990 & 1999 ISBN 0-634-00765-three on books.google.com

- ^ Shep Fields Leader of Big Band Known For Rippling Rhythm Shep Fields Obituary listing his hit recordings including "Cheers For the Memory" in The New York Times on nytimes.com

- ^ Shep Fields Dies - Noted Bandleader - Obituary in Associated Press in the Telegraph Feb.24,1981 on news.google.com

- ^ Thank you For the Memory - Bob Hope - signature song of Bob Promise on genius.com

- ^ Thanks For the Memory listed in The Real Book - 6th edition Hal Leonard, Milwaukee, WI ISBN 978-1-4584-2617-eight on books.google.com

- ^ Thanks For the Memory ranked 762 in the yard most frequently recorded jazz compositions on jazzstandards.com

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "You Go to My Caput". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved xx Feb 2009.

- ^ The Existent Book, Book I, p. 22

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "All the Things You Are". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 99.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Darn That Dream". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Frenesi". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Volume, Volume II, p. 142.

- ^ The Existent Book, Volume Three, p. 158.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "I Didn't Know What Time It Was". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume Ii, p. 180.

- ^ The New Real Volume, Volume Ii, p. 141.

- ^ Tyle, Chris. "I Idea About You". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ "In the Mood". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Volume I, p. 208.

- ^ Schuller 1991, p. 674

- ^ Studwell & Baldin 2000, p. 75

- ^ Listed in The New Existent Volume, Volume III.

- ^ "Moonlight Serenade". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Studwell & Baldin 2000, p. 78

- ^ a b Warner 2006, pp. 284–285

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "Moonlight Serenade". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ The New Real Book, Volume 3, p. 287.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "Over the Rainbow". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Something to Live For". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Van de Leur 2002, pp. 177–178

- ^ Bradbury 2005, p. 49

- ^ Giddins 2000, p. 257

- ^ The Real Book, Volume II, p. 420.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy. "What'due south New". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ The Real Book, Book I, p. 447.

- ^ Studwell & Baldin 2000, p. 151

- ^ a b Yanow, Scott. "Woody Herman". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

Bibliography [edit]

Reference works [edit]

- Banfield, Stephen; Block, Geoffrey (2006). Jerome Kern. Yale Academy Press. ISBN978-0-300-11047-0.

- Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2002). All Music Guide to Jazz: The Definitive Guide to Jazz Music. Backbeat Books. ISBN978-0-87930-717-two.

- Bradbury, David (2005). Duke Ellington. Haus Publishing. ISBN978-1-904341-66-6.

- Clayton, Buck; Miller Elliott, Nancy (1995). Buck Clayton's Jazz World. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN978-1-871478-55-6.

- Daniels, Douglas Henry (2006). One O'Clock Leap: The Unforgettable History of the Oklahoma City Blue Devils. Beacon Press. ISBN978-0-8070-7136-6.

- Dregni, Michael (2004). Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend. Oxford University Printing US. ISBN978-0-19-516752-8.

- Driggs, Frank; Haddix, Chuck (2006). Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop – A History . Oxford University Press Usa. ISBN978-0-19-530712-two.

- Forte, Allen (1995). The American Popular Carol of the Golden Era, 1924–1950. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-04399-9.

- Furia, Philip (1997). Ira Gershwin: The Fine art of the Lyricist . Oxford University Press Us. ISBN978-0-nineteen-511570-3.

- Giddins, Gary (2000). Visions of Jazz: The Offset Century . Oxford University Press US. ISBN978-0-xix-513241-0.

- Gioia, Ted (2012). The Jazz Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-19-993739-4.

- Greenberg, Rodney (1998). George Gershwin. Phaidon Printing. ISBN978-0-7148-3504-4.

- Grudens, Richard (2005). The Italian Crooners Bedside Companion. Celebrity Profiles Publishing. ISBN978-0-9763877-0-one.

- Hersch, Charles (2008). Subversive Sounds: Race and the Birth of Jazz in New Orleans. Academy of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-32867-half dozen.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2007). The Rodgers and Hammerstein Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-0-313-34140-3.

- Hodeir, André; Pautrot, Jean-Louis (2006). The André Hodeir Jazz Reader. University of Michigan Press. ISBN978-0-472-06883-8.

- Kirchner, Bill (2005). The Oxford Companion to Jazz. Oxford Academy Press US. ISBN978-0-xix-518359-seven.

- Schuller, Gunther (1991). The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930–1945. Oxford Academy Press US. ISBN978-0-xix-507140-five.

- Shaw, Arnold (1989). The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920s. Oxford University Press United states of america. ISBN978-0-19-506082-9.

- Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-0-7434-6330-0.

- Studwell, William Emmett; Baldin, Mark (2000). The Big Band Reader: Songs Favored by Swing Era Orchestras and Other Popular Ensembles. Haworth Press. ISBN978-0-7890-0914-ii.

- Studwell, William Emmett (1994). The Popular Song Reader: A Sampler of Well-Known Twentieth-Century Songs. Routledge. pp. 56–57. ISBN978-1-56024-369-iv.

- Sudhalter, Richard M. (2003). Stardust Melody: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael. Oxford University Printing US. ISBN978-0-19-516898-three.

- Tucker, Marker; Ellington, Duke (1995). The Duke Ellington Reader. Oxford Academy Press US. ISBN978-0-xix-509391-9.

- Van de Leur, Walter (2002). Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn. Oxford University Press US. ISBN978-0-19-512448-iv.

- Warner, Jay (2006). American Singing Groups: A History from 1940 to Today. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN978-0-634-09978-half-dozen.

- Wilder, Alec; Maher, James T. (1972). American Popular Vocal: The Cracking Innovators, 1900–1950. Oxford University Press U.s.a.. ISBN978-0-19-501445-seven.

False books [edit]

A false book is a drove of musical lead sheets intended to aid a performer quickly acquire new songs.

- The New Real Book, Book I. Sher Music. 1988. ISBN978-0-9614701-4-two.

- The New Real Book, Volume II. Sher Music. 1991. ISBN978-0-9614701-seven-three.

- The New Real Book, Volume III. Sher Music. 1995. ISBN978-1-883217-thirty-3.

- The Real Book, Volume I (6th ed.). Hal Leonard. 2004. ISBN978-0-634-06038-0.

- The Existent Volume, Book II (second ed.). Hal Leonard. 2007. ISBN978-1-4234-2452-9.

- The Existent Book, Volume 3 (2nd ed.). Hal Leonard. 2006. ISBN978-0-634-06136-iii.

- The Existent Jazz Book. Warner Bros. ISBN978-91-85041-36-vii.

- The Real Vocal Book, Volume I. Hal Leonard. 2006. ISBN978-0-634-06080-9.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_1930s_jazz_standards

0 Response to "Better Take a Look Again Jazz Standard"

Enviar um comentário